Nestled next to City Creek Center mall in downtown Salt Lake

City is a somewhat unassuming Art Deco building. But this multi-story terra-cotta covered edifice is a lot more important to Salt Lake City’s past and present than it

may let on. What is it? The telephone exchange building.

|

Salt Lake City's telephone exchange building.

Corner of State Street and 100 South. |

Today just about everyone takes for granted the

telecommunications network that connects our world. It is so out of sight that few

give any thought to it, except perhaps for when it temporarily stops working. We

simply pick up a phone or type an internet address into our web browser

and expect it to work, without much thought as to how it does so.

You might be asking what exactly is a telephone exchange? It is essentially a switch that connects two telephones. I will explain the process, but be warned, this is somewhat oversimplified. If you have

landline telephone service, there is a wire that runs directly from your house

(either underground or on poles) to a building housing the telephone exchange.

This building is usually called the “Central Office.” Large cities may have

several exchanges and buildings, whereas a number of small towns may actually share an

exchange. If you are in Utah, it is likely your city has an small, unassuming, and often windowless

building which serves as the local central office. One easy way to identify an

exchange is the prefix number (For example, 795 is the prefix for everyone on

the Fillmore, Utah exchange, and 785 is the prefix for everyone on the Pleasant

Grove, Utah exchange. At one time exchanges actually had names, so Pleasant

Grove was SUnset-5, with the “S” and “U” eventually becoming 78. (Keep in mind these are prefixes, not area codes, which

came later and cover a much larger area.)

As the wire enters the central office it is connected

to switching equipment. In the early days the switching was done manually by a

woman working at a switchboard and later automatic switching, by way of dialing telephone numbers was invented. If

you call someone who is connected to the same exchange (so

usually in the same town) you will simply be connected through a switch in the

same building. If you call someone who is further away, your exchange will have to connect to their local exchange which will then connect you

to their telephone. Calls which require you to connect to more distant exchanges are “toll” calls where your

regular telephone subscription does not cover the cost and you have to pay extra–commonly called a long-distance fee. Cell phone towers connect to a similar building, known as a

Mobile Telephone Switching Office.

While the exchange building seen today is not the original central office in Salt Lake City, it is interesting to note that every Bell

System telephone exchange in the city has been on this block (block 75). This post will not really be a history of the telephone system in Salt Lake City, but

rather a history of the exchange buildings and their growth.

On Friday, April 22, 1881 the first telephone exchange

office opened for business in Salt Lake City.(1)

The office and its switchboard were housed in the Western Union Telegraph

Office on Main Street. (This telegraph office is also where the all-important final

connection in the

first transcontinental telegraph was made.) The telephone system proved so popular that within weeks additional

equipment had to be sent for and the company quickly outgrew its space in the

telegraph office. That summer the office moved just a few doors south, to the

third floor of the Deseret National Bank building.(2)

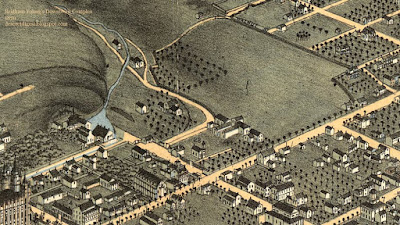

|

Salt Lake City telegraph office and first home to the telephone

exchange in 1881.

Source: Wikimedia Commons. |

|

The Deseret Bank Building and home to the telephone exchange

from 1881-1895. Corner of Main Street and 100 South.

Notice the framing for telephone wires on the roof of the building.

Source: Utah State Historical Society Classified Photo Collection,

number 19423. |

The exchange remained in the Deseret Bank building until

January 1895, when it moved into its own specially designed home on the

opposite side of the block, at 56 South State Street. Built just north of the famous

Salt Lake Theatre, the new building was three stories high and was made as fireproof

as possible.(3) The

building’s new switchboard was a top of line replica of one exhibited by

AT&T at the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893. The board, which cost $12,000, was capable of handling 3,000 “instruments” (they

called a telephone an instrument and you didn’t actually own an instrument,

just rented it from the telephone company).(4)

One of the more dramatic changes to the telephone system

that accompanied the new building was the burying of the telephone lines as they

approached the building. The lines entered conduit at the intersection of State

Street and 100 South, then traveled underground to enter the exchange

building.(5) As you can imagine, having hundreds and eventually thousands of

individual wires running into a single building on poles was unsightly and impractical, and they were better protected underground. Another improvement was that

customers no longer had to ring their party after the exchange had made the

connection, rather the operator would do the ringing.(6) The Salt Lake Tribune called this new way of

placing a call “to telephone a la metropolitan.”(7) Double wire, still a telephone standard, was also introduced at the time.(7)

The new building was ready for business by the middle of

January 1895, with the employees receiving training for the new switchboard on the 15th. The switchover happened on Saturday, January 19, 1895, with the hope it could be “made without the knowledge of the subscribers."(8)

Much like what had occurred in former locations, the space quickly became in

inadequate, and by 1900 the telephone company was already talking about an addition

to their new building.(9) Construction on an

addition to the north side of the building, which almost doubled its size, was

underway by 1902.(10) The Salt Lake Telegram reported that once the addition was completed, the first floor of would include the local contract office, storage

room, and a large bicycle storage area for 50 bikes. The second floor would

include the company’s general offices, and finally the third floor would

include a huge new switchboard, engineer’s office, and wash and cloak

rooms for the operators. The wall of the old building would be removed on the

third floor to allow for a large open space spanning both the original building and its new addition.(10)

The 1902 switchboard would allow for a new feature. No longer

would you have to ring the central office by way of the bell crank, but when

you lifted the receiver a small indicator on the switchboard would flip and the operator would know you needed to place a call. All

old instruments were gathered up and replaced with new ones capable of this

feature.(11)

But in just a few years time—yet again—the telephone business in the city outgrew the

building. By the summer of 1906 plans were already

underway to add a rear addition, basement, and two stories to the top of the

building.(12) New switchboards (one for local calls and one for long distance) were

to placed on the new fifth floor, with a glass partition separating the two.

The additions were completed and the new switchboard went into operation on

Sunday, October 6, 1907. If you’re interested in the final layout of this

building I highly suggest reading an article from the

Salt Lake Herald entitled,

Bell Phones Working Through New Switchboard. Apparently at the time the

switchboard was the longest in the world.(13)

|

The telephone exchange building at 56 South Street Street,

as seen in its different stages of expansion.

Source: Utah State Historical Society Classified Photo Collection,

numbers 05584, 05585, 15080. |

When the 1895 building was constructed, it was placed just

north of the Salt Lake Theatre. A landmark of downtown, the theater was run by

the Salt Lake Dramatic Association. The association, whose largest stockholder was The Church of

Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, sold the theater to the telephone company in 1928 for $200,000.(14) The last show, the opera Robin

Hood, was held in the theater on October 20, 1928.(15) By the end of December 1928 razing

of the theater was nearly completed.(16) Even though the theater was gone, the telephone company didn't build anything new right away. In fact, a service station was built on the site of the theater. It was not until nearly a decade later, in January 1939 that the telephone company finally announced construction of a new building on

the lot.

The new exchange building, today at 70 South State Street, would include three stories and a basement. The

basement would be where the wires would enter the building and would also include

emergency generators. The main floor would house the business office, the

second floor would have space for long distance and information, and the third floor would

contain the dialing equipment. (The entire building was designed so additional

floors could be added.) Of major interest was the additional announcement that dialing would be coming to Salt Lake City. Apparently up to that time it was still all operator-based routing of phone

calls. At the time, the Salt Lake Tribune reported that it was “the largest

manually-operating exchange in the world.”(17)

Construction

started about March 1939 and the business office in the new building was opened on

Monday, December 18, 1939 (although the article pointed out that the new equipment would not be operating until the following August).(18) Once the new equipment was installed and running, at midnight on August 17,

1940 the switchover was made and Salt Lake City finally got dial service operating out of the new central office.

|

An advert introducing both the new exchange

building and dial service.

Source: The Salt Lake Tribune, 4 August 1940. |

In tribute to the old Salt Lake Theatre, a large plaque—about seven feet high and four feet wide—was placed in a niche on the east side of

the new exchange building. The plaque was sculpted by Mahonri Young, a grandson of Brigham Young. It was dedicated during the Church’s October

General Conference in 1940.(19)

|

The Salt Lake Theatre plaque on the east side of

the telephone exchange building. |

This building was specifically designed to support

additional floors and in 1947 three more were added.(20) At the same time an addition to the north side, spanning all six stories, and including a new entrance along State Street was constructed. In 1956–1957 the building was expanded yet again, this time

a three-story addition was made to the north of the building.(21)(22) And finally, in 1962–1963 three more stories were added on top of the 1956

addition.(22) This was the last addition made to the building in which the architecture was made to blend in with the original 1939 construction. These various additions are highlighted in the image below. (A concrete addition, with a stamped design—a map with LED lights—was added on the north side sometime circa 2002, but I cannot find out exactly when or why.)

|

| The various additions, along with the year construction started. |

|

The telephone exchange building at 70 South Street Street

as seen in its different stages of expansion.

Source: Utah State Historical Society Classified Photo Collection,

numbers 26046, 62598b, 25162. |

The next time changes came to the building were in large part because of the construction of the ZCMI Center Mall on the same block. Up until this time both the 1895 and 1939 buildings (and their additions) had stood side by side; this is shown on the 1950 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map clipping below.

|

Both buildings (connected by tunnel) can be seen on

this Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1950.

Source: J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

Unfortunately, the 1895 building was damaged

during the construction of the ZCMI Center Mall and in the fall of 1976 it was torn down.(23) While construction on ZCMI was occurring, a new addition on the west side of the

exchange building was built, although no effort was made to match it to the exterior of the main building. This addition initially held long distance switching equipment.(24)

|

The south side of the building. The large gray building

at left is the 1970s addition. |

It would be some time until anymore exterior changes were made to the building. In 2006, the Church of Jesus Christ announced that they would be tearing down the 1970s ZCMI Center Mall and replacing it with a new mall, called City Creek Center. The new mall was constructed between 2006–2012, and much like during the construction of the first mall, the surrounding work would mean new changes for the telephone exchange building. The changes were not as dramatic as seen in the past, but they included "reskinning" the 1970s addition by replacing its brown block exterior with a smooth grayish exterior (as seen in the image above), an exterior mimicking the terra-cotta on the street facing sides of the building was added to the north side of the main exchange building, and the tower connecting the building to AT&T's microwave network was removed.

Since the construction of City Creek Center, little has changed on the exterior of the building. Today the secured entrance boasts the logos of both AT&T and CenturyLink. The building is likely home to CenturyLink's local exchange and houses entrance points into AT&T's large data network (which is used for much more than voice calls). This blog post focused mostly on the changes to the exteriors of the buildings, and while the interior "guts" have likely seen many more changes and will continue to see them, information is hard to obtain. This is in large part due to the need to secure the network and also because the changes are so technical and happen fairly regularly.

It is hoped this post has given the reader a better understanding of how Salt Lake City's telephone system has grown over the years.

Works Cited

1. "The Telephone." Salt Lake Herald, 23 April 1881, 3.

2. "Telephone Exchange." Salt Lake Tribune, 1 January 1882, 13.

3. "The Telephone Building." Salt Lake Herald, 24 January 1894.

4. "Construction to Be Resumed." Salt Lake Herald, 15 May 1894.

5. "Making Very Rapid Progress." Salt Lake Herald, 29 September 1894.

6. "Less Rings Necessary." Salt Lake Herald, 10 January 1895.

7. "On A Metropolitan Basis." Salt Lake Herald, 20 January 1895.

8. "They Want A Telephone." Salt Lake Herald, 16 January 1895.

9. "Will Enlarge Its Building." Salt Lake Tribune, 6 January 1900. (See also mention of an addition in "Fourteen Thousand Miles of Wire to go Underground." Salt Lake Herald, 7 September 1901.)

10. "Big Improvements in the Telephone Building." Salt Lake Telegram, 12 June 1902.

11. "3,500 Connections Made In 10 Minutes." Salt Lake Telegram, 19 August 1902.

12. "Bell Telephone is Enlarging Plant." Salt Lake Tribune, 8 July 1906.

13. Herbert J. Hackenburg, Jr. Muttering Machines to Laser Beams: A History of Mountain Bell, (Denver, Colorado, Mountain Bell, 1986), 79.

14. "Telephone Co. Purchases Salt Lake Theatre." Salt Lake Telegram, 16 April 1928.

15. "Final Salt Lake Theatre Show to be Held Oct. 20." Salt Lake Telegram, 7 October 1928.

16. "Wrecking of Salt Lake Theatre Nearly Finished." Salt Lake Telegram, 26 December 1928.

17. "Phone Company Plans Two Buildings in S.L." Salt Lake Tribune, 30 January 1939, 1&3.

18. "Throngs Visit Offices of Phone Firm." Salt Lake Tribune, 19 December 1939.

19. "Plaque Enters Theater Site Niche Today" Salt Lake Tribune, 24 September 1940.

20. "Builders Finish Exterior of Phone Edifice." Salt Lake Tribune, 7 December 1947, 6B.

21. "S.L. City, County Building Top $15 Million as ’57 Bids Adieu." Salt Lake Tribune, 29 December 1957.

22. "MST&T to Add Three Floors." Salt Lake Tribune, 9 September 1962.

23. "Telephone Landmark Falls After 81 Years." Salt Lake Tribune, 2 October 1976.

24. "Mountain Bell Plans Year of Expansion." Salt Lake Tribune, 27 January 1974.